In 40th year, Colorado Springs nonprofit continues legacy of outdoor guardianship

February 8, 2021

By Seth Boster: seth.boster@gazette.com

On a sunny, summer day in 2018, Hartley Hesse and her sister, Laurel, hiked high on Cheyenne Mountain to build a bench at a scenic overlook.

It was to commemorate their late father, the man responsible for designing long-anticipated trails around this iconic summit in Colorado Springs — and responsible for the local group leading construction, Rocky Mountain Field Institute.

Mark Hesse, the renowned mountaineer and Springs native, died in 2014 at the age of 63.

He was doing what he loved: climbing. Just as much, he loved giving back: building and maintaining trails that could withstand the outdoor masses he saw rising in Colorado and inspiring the next generation of stewards. This was his purpose for RMFI, which is celebrating its 40th-year anniversary.

The Cheyenne Mountain trails were examples of premier jobs the nonprofit has overseen. But these trails had extra meaning. These were among the last to come to life from the founding father’s vision.

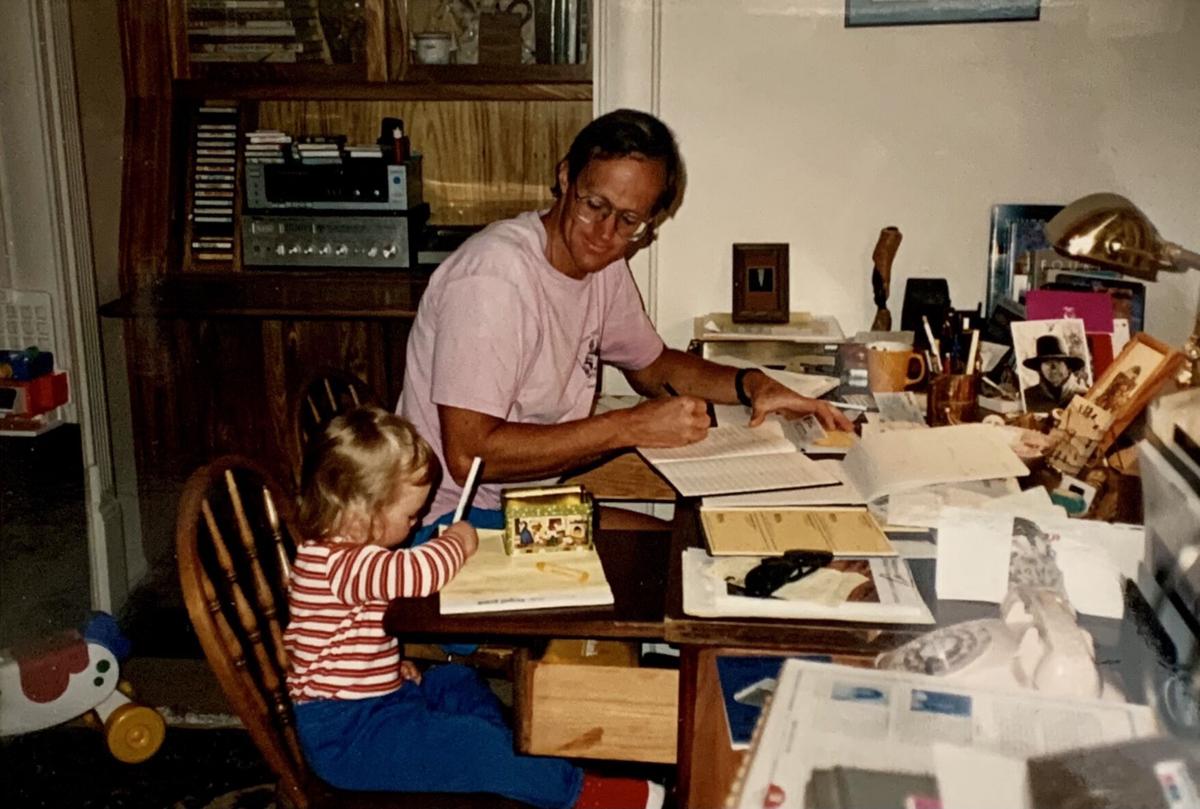

In its 40th year, Rocky Mountain Field Institute is remembering its founder, Mark Hesse. Photo courtesy Rocky Mountain Field Institute

And so there his daughters were, seeing the task finished. Today the bench is easy to miss, because it’s not a bench in the traditional sense. It’s more of a rock slab, blending in with the natural environment, fashioned by the same back-bending means Hesse took to sustainable, rock-made paths at high elevations.

The Hesse sisters had a place to rest after the work.

“It was really emotional,” Hartley said. “My dad’s legacy will always be in the trails he made, but my sister and I really wanted to make a tribute to him with our hands in the same way he was doing this kind of work.”

And they’re pleased to see the work continue. Pleased by every email that comes to them and RMFI supporters everywhere, updates from the organization that has grown by leaps and bounds since the 1980s beginnings in Hesse’s home.

For a while, it was just he and Liz Nichol, a family friend and fellow outdoor enthusiast. She joined him when he was the group’s sole full-time worker. Her job was to manage the books and grow the volunteer base.

Previously, “it was just Mark calling his friends and saying come on out,” Nichol said.

They came to Garden of the Gods and other beloved places Hesse saw falling into eroding ruin: Shelf Road, now the climbing epicenter in Cañon City, and Utah’s famed Indian Creek area.

Later, Hesse rallied fellow climbers to the bases of 14,000-foot peaks in southern Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo range. There, resource-strapped land managers toiled over worsening damage from foot traffic.

Hesse saw it firsthand. Around the globe, yes, on his travels recording historic ascents, but also around his home city, which was perhaps more disturbing to him. He grew up in the Springs in the 1960s, the era of the Wilderness Act.

“He was concentrating on how the environment around the city was changing,” Hartley Hesse said, “and how trails were being changed, and not for the good.”

The wild should be wild, he believed, indeed “where man himself is a visitor who does not remain,” as that 1964 act stated. But what was man’s role in keeping it that way? “It weighed heavy on him,” his daughter recalled.

Mark Hesse’s small army of activists would talk shop over pizza and beer in an attachment of his home; RMFI, initially American Mountain Foundation, had outgrown the grant writing center that was his basement. Pizza and beer were necessary costs when funds were low.

“I’d have to check the bank to see if there was enough money,” Nichol said.

So imagine her surprise when she retired from RMFI just a few years ago. By then, the operating budget exceeded $1 million.

Now the budget is closer to $2 million and showing no signs of reversing exponential growth from the past decade.

In the seven years that Jennifer Peterson has been executive director, RMFI reports quadrupling in size. That’s in staffing; Peterson counts seven permanent workers and 30 seasonal. And that’s in funding from donors and contracting agencies such as the city of Colorado Springs, El Paso County, Colorado Parks and Wildlife and U.S. Forest Service.

“A big priority when I started was making sure all of our land managers knew who we were and what we provided,” said Peterson, who came with a Ph.D. in natural resource management.

For 2021, work is expected at 23 sites locally and regionally, including on the back side of Pikes Peak, where RMFI is building a trail to replace the deeply incised one along the Devil’s Playground route.

More than ever under Peterson, RMFI has been at the table for high-profile, highly scrutinized projects. One was the Bear Creek collaboration that saw the Forest Service reroute popular trails in the city’s southwest mountains. More recently, there was the city’s purchase of a quarry above Manitou Springs — a deal made at the end of a RMFI-led initiative that convened stakeholders to plot a long-sought return of recreation in Waldo Canyon.

RMFI partnered with the Forest Service in revegetating and restoring that landscape ravaged by the 2012 wildfire. After another fire a year later, Black Forest needed help. Peterson considers those twin disasters “unfortunate” springboards — events that brought RMFI to the forefront of the public eye.

“The outpouring from the community, I mean, our phones were ringing off the hook,” Peterson said. “’How do we help? How do we give back? How do we restore these areas?’”

The nonprofit’s growth can also be attributed to sheer demand for the niche work, said Mike Smith. He spent the past 10 years on the RMFI board after retiring from a Forest Service career dating back to the 1970s.

“The money in land management agencies has been going down. The workload far exceeds the money and the number of government employees available,” he said.

Hence, he explained, the widening gap to fill for RMFI and other nonprofits like Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado and Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, which Hesse also helped found.

“So these groups are stepping up in three ways,” Smith said. “They’re bringing in help, their own sources of money, that allows you to expand the public land budget. They’re bringing in crews to actually get the work done. And the third thing is they’re instilling this sense of stewardship, creating this ethic in the people they draw on to work on these projects.”

Before today’s supervised youth crews and volunteers, Smith grew familiar with Hesse’s band of scrappy, spirited climbers. They set up camp in the Sangre de Cristos, where Smith, the official wilderness manager assigned to the area, had identified work to be done.

“Hard trails” were an emerging concept at the time — rock-defined paths armored against erosion. The idea was “maintaining the wild character of the land in the midst of this restoration and improvement work,” Smith said. “Balancing that with the wild character.”

From Humboldt Peak and the Crestones, RMFI has continued the laborious, technical work in the southern range. Last year, the organization declared a new trail finished on Kit Carson Peak.

It was another update that pleased the Hesse family. It’s no surprise the career paths taken by the man’s daughters: Laurel works for the American Civil Liberties Union while Hartley is committed to marine biology, teaching about and researching threats to the oceans.

“We’re both hoping to uphold that legacy,” Hartley said. “Just trying to be part of our communities and educate people on what good they can do.”

Good was the work on the bench high on Cheyenne Mountain, in honor of their father.

“We had talked about putting a plaque on it,” Hartley said.

But they thought better, she said.

Better to keep it wild.