Waldo Canyon History

April 26, 2022

Written by Eric Swab. Reposted from the Trails and Open Space Coalition Website.

***

(Eric Swab offers a fascinating account of the man behind of the region’s most beloved canyons. A man who swallowed documents, got into gun-fights, had several near-death experiences, borrowed money 14 times and it would seem attempted to swindle the federal government)

About one mile past the Cave of the Winds entrance on highway US24 is the mouth of Waldo Canyon. It is a narrow opening in the rocky cliffs, and easy to miss. Another third of a mile up the highway is the now closed parking lot for the once popular Waldo Canyon trail head.

Who was William A. Waldo? To paraphrase a reporter writing about Mr. Waldo in 1891, “As critical information about the principal party of this story could not be found, this account of his life may not be perfect in every particular.”

The 1885 Colorado Census informs us he was born in New York about 1850. For the next 30 years we know nothing about his whereabouts nor what he did for a living. In 1881 he showed up working in a Gypsum quarry near Colorado City. We know this because he was very nearly crushed to death by a rock fall there.

To quote the account in the Weekly Gazette, “At the time the accident occurred three men, Messrs. Milton Yarberry, W. A. Waldo and O. H. Ingraham, were at work in the quarry. They had just discharged a blast and were busily engaged in picking off the loose rock… Mr. Waldo was at work near the base of the wall and Mr. Yarberry was standing on a scaffold, when Mr. Ingraham, who was at work some distance off, shouted: ‘The whole wall is coming! Jump for your lives!’ No sooner had the warning been uttered than the mass fell with a terrible crash. Mr. Yarberry jumped as soon as he heard the shout… but he was caught beneath a large rock and held fast, his left leg being fastened beneath the debris. Ingraham at once came to his assistance but finding that he could not relieve him alone he started off for the purpose of summoning aid. Both Yarberry and Ingraham supposed… Waldo’s lifeless form was lying beneath the mass of rock. Soon after… Waldo presented himself upon the rocks above Yarberry’s head… he set to work and finally succeeded in relieving him. Both men, although somewhat bruised, were able to walk to Colorado City.”

Apparently, Waldo had flattened himself against the gypsum cliff and the falling rock had pilled up in front of him. Unhurt, but seemingly trapped, he was able to crawl through the spaces between the fallen rock to safety. So, in 1881 we find the quick-witted Mr. Waldo working as a laborer.

The 1885 Colorado Census also tells us that Mr. Waldo is living with Louis A. Schamp, his wife Kate and son Will, in El Paso County. Both of Waldo’s parents were born in New York, but nothing more is known about them. William was then working at a dairy ranch. It is interesting to note that of the ten people boarding with the Schamps, four were soldiers with the U. S. Army Signal Corps. Sargent Harry Hall was in charge of the signal station on the summit of Pikes Peak, Private John P. Ramsey was his assistant. George Curtis and Mr. Van Vorst were also corpsmen assigned to the Signal Station.

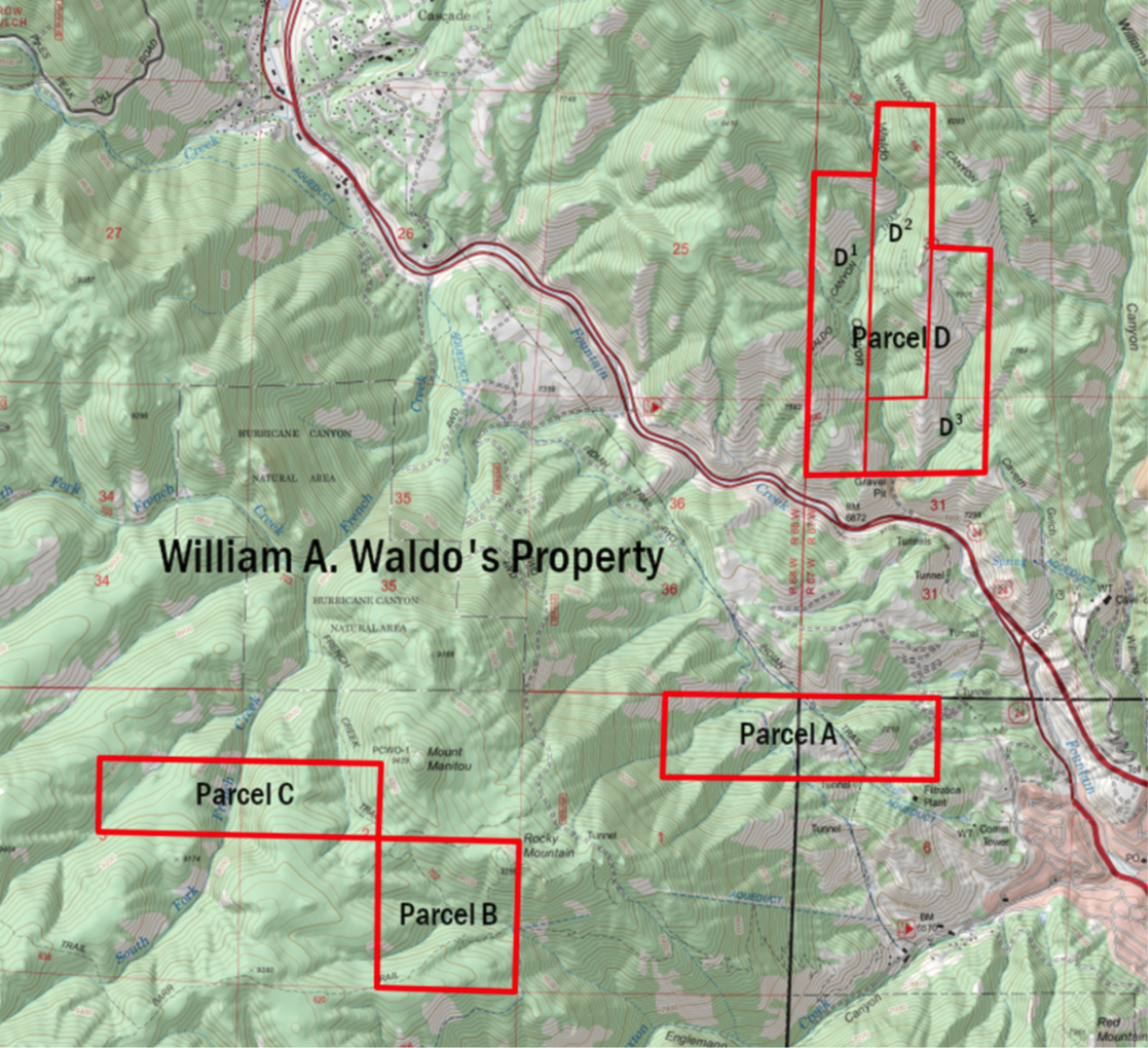

On May 5, 1885, William A. Waldo filed a Pre-Emption Homestead claim for 176.26 acres, ¼ mile north of what would become the Manitou Incline (Parcel A on the map). Five months later, on October 10, 1885 Mr. Waldo filled Homestead claim for 160 acres centered on the confluence of 3 branches of Rock Creek (now known as “No Name Creek”) and ¼ mile south of Mount Manitou (Parcel B). A Pre-Emption Homesteader was required to occupy and cultivate the land for six months and to pay $1.25 per acre before filing for another 160 acre claim. Mr. Waldo was a little less than a month short of meeting that requirement.

Waldo did not receive his patent for Parcel A, until March 29, 1889. Never the less he agreed to sell the property to Norman C. Jones, on September 5, 1886. At that time Mr. Waldo was living on Parcel A. In the sale agreement between Waldo and Jones was the provision, “to let him [Waldo] occupy said ranch as he now is doing for one year rent free.”

Mr. Waldo also converted Parcel B to a cash entry on August 18, 1890, paying the $1.25 per acre, and was issued a patent on April 23, 1891. This Parcel B would become the core of the Fremont Forest Experiment Station (aka Fremont Experimental Forest) in 1909.

In 1890, having reached his limit of 320 acres, Mr. Waldo devised a tactic for acquiring more government land. He purchased the Pre-Emption claims of other people shortly after they had filed. It can’t be said with certainty that he was friends with the entry men whose claims he bought, but his procedure certainly suggests he was.

On June 4, 1890, John W. Howell claimed 160 acres immediately northwest of Waldo’s Parcel B, paying $200 for a Pre-Emption. On the June 25th Waldo purchased John W. Howell’s claim for $550, (Parcel C on the map).

On July 28, 1890, Belle Clay filed a Pre-Emption claim on 154.23 acres in what we know as Waldo Canyon, paying $192.79. On August 9th Waldo purchased her claim for $300. (Parcel D1)

On September 16, 1890, Sarah Tolliver filed a Pre-Emption claim on 160 acres immediately east of Belle Clay’s claim in Waldo Canyon, paying $200. On October 2nd Waldo purchased her claim for $450. (Parcel D2)

On August 6, 1890, Albert L. Bateman filed a Pre-Emption claim on 160 acres immediately east and south of Sarah Tolliver’s claim, also in Waldo Canyon, paying $200. On December 3rd Mr. Waldo purchased Albert L. Bateman’s claim for $500. (Parcel D3)

The last three purchases above, gave Mr. Waldo 474 acres comprising most of what we consider to be Waldo Canyon. It seems obvious that Mr. Waldo was engaged in collusion with Clay, Tolliver and Bateman, to gain government land. (Parcel D)

William Waldo established a hog ranch in Parcel D. To feed his hogs he hauled garbage from Manitou. Between 1893 and 1896 he borrowed money 14 times, securing the loans with chattel mortgages secured by his cattle, hogs, horses, and crops of potatoes, and hay. He also borrowed money from such luminaries as William S. Jackson, a founding father of Colorado Springs and Harriet Wheeler, likely the wife of Jerome B. Wheeler, a Manitou banker and businessman. These loans were secured by mortgages on Waldo’s real property.

In Green Mountain Falls there was a law requiring the impounding of livestock that ran loose. Mr. Waldo apparently violated that law, because he filed a law suit challenging it. He was supported financially by people who agreed with his point of view. The city marshal had reason to serve a warrant on Mr. Waldo. Waldo resisted and ran off, while the marshal fired several shots after him, missing his mark. The marshal went to Waldo’s home and a gun fight ensued. No one was hurt, but Waldo escaped again, fleeing to Colorado Springs where he sought protective custody. Unfortunately, the results of Mr. Waldo’s law suite is unknown.

“Mudy” Jones (Norman C. Jones?) held a chattel mortgage on Waldo’s cattle. When a quarrel ensued over the mortgage, Waldo asked to see the document. When Jones handed him the paper, Waldo took it, put it in his mouth, chewed it up and swallowed it!

In a 1937 letter from Paul P. McCord, Acting Forest Supervisor, to Julia C. Stokes, he describes the origin on the name of Waldo Canyon; “Takes the name of an old recluse named Waldo who lived in a hut there during the early days.” William Waldo’s 474 acre ranch in the canyon, reverted to the Forest Service. On February 20, 1900, the Forest Service exchange Waldo Canyon for land owned by William E. Moses elsewhere. Today Mr. Waldo’s hog farm is once again the property of the United States Government.